Many Destinations, One Place Called Home: Migration and Livelihood for Rural Bolivians

When immigration’s impact upon people and places is discussed, images of the world’s big immigrant gateways come to mind, such as New York City, Toronto, or Paris. These cosmopolitan global cities are brimming over with immigrants from many parts of the world. Given less thought are the thousands of localities that produce migrants decade after decade. How do these places manage with large numbers of working-age people leaving? Do migrants return? What impact does steady out-migration have on livelihoods, landscapes, and society? This photo essay explores a region of Bolivia that has been producing international migrants for nearly a century. Southeast of the city of Cochabamba is the Valle Alto, a fertile plain at an elevation of 8,000 feet and surrounded by mountains. This agricultural region is dominated by grain production, especially corn, and in irrigated areas, peaches are grown for domestic markets. There a scores of small villages scattered across the valley floor, but this essay focuses on the villages surrounding the towns of Tarata and Arbieto.

Most of all, this region is known for its migrants. People have been leaving this high valley for decades, moving to Bolivia’s large cities such as Santa Cruz or nearby Cochabamba, settling in the lowland villages of the Chapare and cultivating coca, or emigrating to foreign lands such as Argentina, Brazil, Spain or the United States Migration is part of the rhythm of this valley. To underscore this point, a running joke is told that when the astronauts landed on the Moon, they were greeted by a Cochabambino selling chicha, a corn-based beer that is central to daily life. The image of a rural Andean farmer on the Moon with his pitcher of chicha for sale is funny enough. It is told with a mix of pride for the ingenuity and resourcefulness of Bolivians, and also a tinge of sadness for the necessity to leave the country, or even the planet, to secure a livelihood. Selling chicha in a remote locality affirms the shared belief that though Bolivians may travel vast distances, they are still attached to something essential about their home.

Eulogio and Emma Cespedes from the town of Tarata share a cup of chicha, served in a dried gourd that makes the preferred cup. Like many families in this region, their eight children are scattered, with six living in the United States and two living in the city of Cochabamba. They have expanded their home so that their children and thirty-four grandchildren have a place to stay when they visit.

The Cespedes family is indicative of a demographic trend common in valley. Most of the towns and villages are filled with elderly people or young children, but relatively few people in their prime working ages from twenty to forty-five. It is not unusual for grandmothers to care for grandchildren, while parents seek employment in foreign cities and send remittances back. These monies are used for basic household needs, to purchase vehicles and bicycles, to build homes, or to invest in agriculture.

Although many people leave, new homes are popping up in the small villages of the Valle Alto such as Arbieto, which has had a construction boom. It is estimated that up to one-third of Arbieto adults are working overseas, especially in the United States. They send funds back to build homes that are far larger and more eclectic than traditional structures. Smartly painted and with tile roofing, this two story house stands out from the adobe brick homes surrounding it.

This brightly painted house with mirrored glass and a decorative fence is in the village of Tiataco not far from Arbieto. It was built by migrants, many of whose homes sit empty for most of the year with families returning for Christmas holidays, Carnival, or the summer months of the northern hemisphere. Such homes are clear testaments to immigrant success and the dream of returning home one day.

The Gutierrez Family is another example of the multigenerational aspects of migrant livelihoods. Juan Gutierrez has six children, three of whom where born in Argentina when he migrated there for work in the 1970s. The other three were born in the Valle Alto. In the 1990s he left his grown children to work construction jobs in the United States for three years and then returned to Bolivia, where he lives today. All of his adult children, however, have travelled to the United States, the men working construction and the women in childcare and housekeeping. Juan believes his sons will return, as most do not have legal residence in the United States. In preparation for that return, he has been building them houses, one at a time, with his own labor and the remittance dollars they send. Here he stands before one of the nearly completed houses.

In addition to homes, migrants invest in agriculture. Usually this means capital-intensive production, such as peach orchards or cattle. The Valle Alto is known for its peaches. With migrant dollars, peach orchards have expanded throughout the area. In the village of La Loma, one can seen various migrant investments made from peaches - here, in the foreground - to cattle grazing in the mid-ground, and, in the distance, a new church built with money sent by residents working in the United States.

One aspect of the migrant economy and attachment to place is giving back, especially to the village as a whole. This is most commonly expressed by building churches with contributions from residents working in the United States, Argentina and Spain. New churches are being erected across the landscape and are an important sign of immigrant engagement and commitment to their home villages. Two new churches, which took nearly a decade to build, were largely paid for by migrants. The brick church is in Mamanaca and the painted church is in Achamoco. Both churches have plaques on them acknowledging the contributions of residents working abroad that made these religious edifices possible.

Soccer is another important amenity in which migrants invest. For Bolivians, soccer is a cultural necessity, and towns pride themselves fostering the next generation of players. In the town of Arbieto, migrant villagers purchased land on the edge of town and in a private-public partnership helped to build the valley’s largest soccer stadium next to the Simon Bolivar high school. The President of Bolivia, Evo Morales, visited this field and celebrated the accomplishment of immigrant dollars, local investment, and state funds. As a sign of changing times, young girls also play soccer in the Valle Alto as seen here.

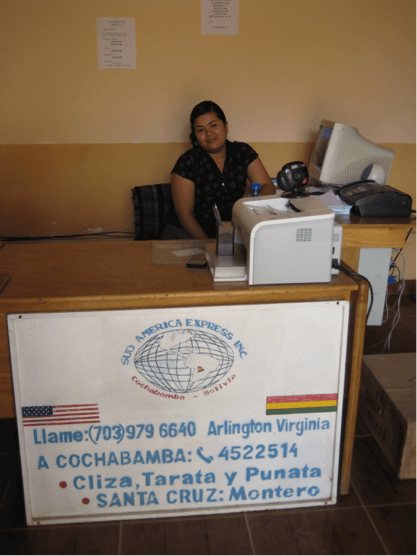

With more capital and technology, it is easier for families to communicate via cell phone, the Internet, or Skype. That still does not ease the pain of having loved ones far away for long periods of time. Other aspects of the migrant landscape are colonial buildings repurposed to support an internet café or to support a remittance-service business in which funds from families in the United States are sent directly to families in the Valle Alto. It is estimated that over $1 billion is sent to Bolivia each year by emigrants living abroad. In the Valle Alto, the typical household with a member working abroad receives $1,500 annually. This is a significant sum of money when one considers that the per capita gross national income in Bolivia is around $2,800.

Part of the immigrant experience is the struggle to maintain connections over great distances. Folkloric dancing is one important way in which children born of Bolivian parents and now living in the United States are exposed to Bolivian culture. In this picture, Bolivia children are participating in a Bolivia festival held each August in northern Virginia. Events such as these draw thousands of immigrants and their children who desire to maintain their connections to a far away home. Another strategy is to have beauty pageants, crowning a Miss Bolivia in the United States.

For those that return to the Valle Alto, reintegration has its challenges. In Arbieto, a long-term migrant who worked for over two decades in Florida, is now the mayor. Don Diogenes runs the local government, tends his peach orchards, and manages his large home. And yet, most of his family has remained in the United States. He told me that he owed it to his community to return.

In the global age we live in, where rural people travel vast distances in search of higher wages, many places like the Valle Alto exist. Some migrants leave never to return, yet most do return in some form or another, either for short visits or virtually through the flow of resources. Navigating lives across borders is not easy, but no matter where the residents of the Valle Alto travel, in their hearts there is still one place called home.