Urban Agriculture in Helsinki, Finland

Finland has become a predominantly urban society. When Finland gained its independence in 1917, only 10 percent of the population lived in urban areas. By 1960 that figure had risen to 55 percent, and presently 70 percent of Finns live in urban areas, according to the Finnish Environmental Institute. Yet most Finns, even those living in cities, have close ties to their cultural heritage and agricultural roots in the countryside. This photo journey explores the spaces, places, and practices of urban agriculture (UA) in Finland’s capital, Helsinki. The city sits at latitude 60.6˚ N and has approximately 600,000 residents. This might not seem like a place well suited for urban agriculture, but an enthusiastic population of growers and the long summer days make this a hotbed of UA development. UA has over a century-long history in Helsinki, and it is embedded in the fabric of the city through zoning regulations. Over the last decade, the number and types of projects have increased rapidly through both municipally supported and grassroots efforts. Grassroots UA projects include box and sack gardens in interstitial spaces, and the establishment of Finland’s first Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) project. This photo essay illustrates how each of the four main types of UA projects found in Helsinki---cottage allotments, allotment gardens, box gardening, and CSAs---fit into its urban landscape.

Helsinki is an interwoven tapestry of built and green space. The downtown is a tightly packed collection of five- to seven-story buildings. However, even in the city center there is still greenspace, with numerous parks and pockets of forest. As you move away from the center, apartment buildings get taller and the green spaces get larger. By the edges of the city, each building is surrounding by its own parklike green space.

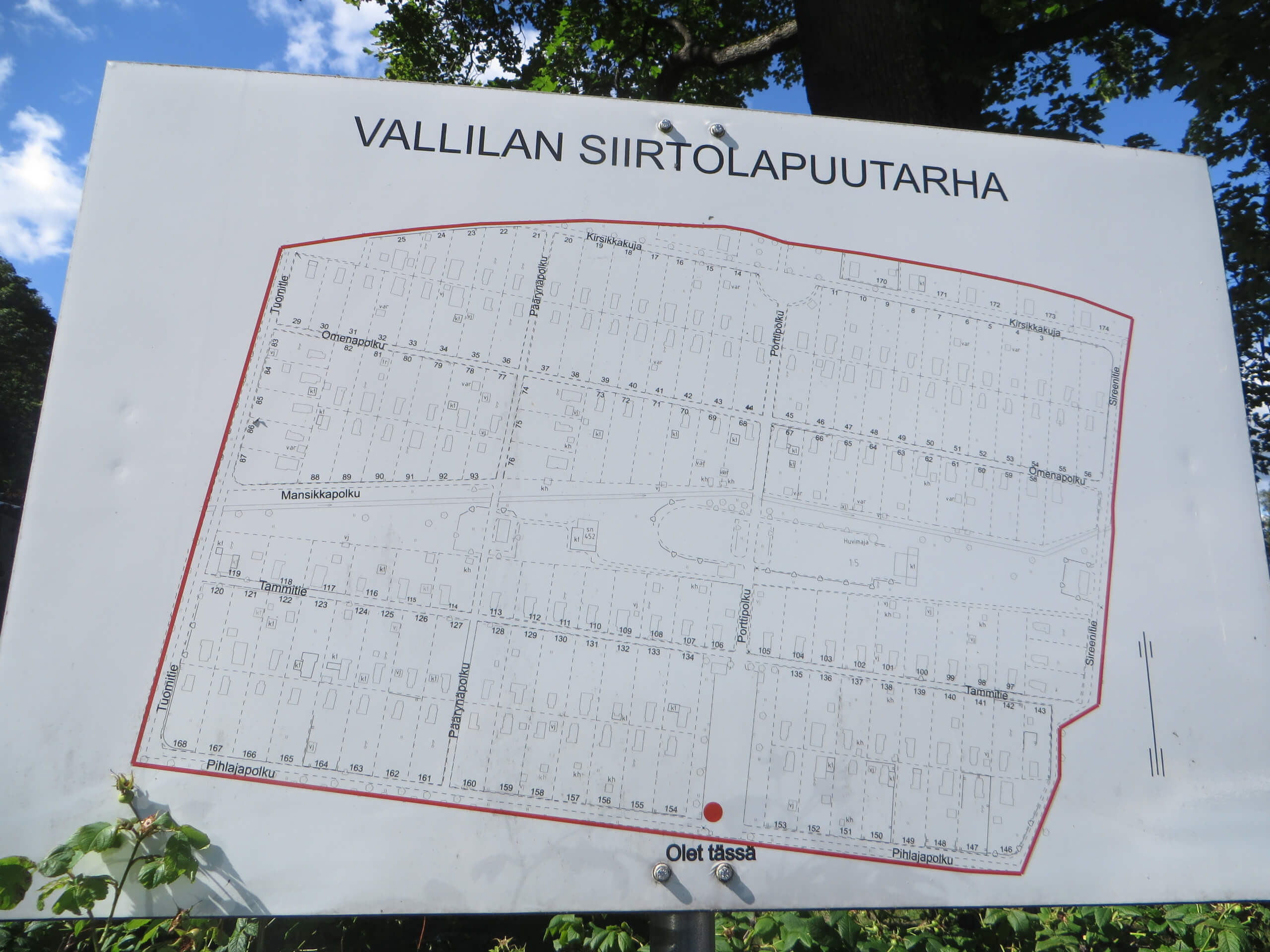

The oldest type of UA in Helsinki is a Siirtolapuutarhat, which translates to “colony gardens,” but in casual speech they are called cottage allotments. The first garden was founded in 1918 and at present there are nine gardens with a total of 1,926 plots. These gardens are a mix of public and private space. The paths that run through the gardens are designated in the city plan as parkland and anyone is allowed access. However, the individual cottages and gardens are private.

The grounds of the gardens are designed to look like miniature villages, complete with whimsical street names, such as Pear or Strawberry lanes. The average-size plot is about 3,000 square feet and the cabins vary in size. There are no cars allowed in the gardens, yet the community restrooms, showers, and saunas can be located quite far from an individual cottage. Bicycles, therefore, are the preferred mode of transportation.

Cottage owners are encouraged by the cottage association to live at their cottage for the duration of the summer season, from May to September. The cottages enjoy many municipal services, including mail delivery directly to the front door.

In addition to the cultural and aesthetic values of the cottage allotments, they also provide a refuge in the city for Helsinki’s bees. Hives are a common sight on garden grounds.

The second oldest type of UA in Helsinki is called Viljelyspalstat, translated as “plantation plots,” commonly referred to as allotments. These allotments were formalized in the municipal plan in the early twentieth century as a place for the increasing population of urban dwellers to cultivate food. The plots are owned by the city and the space is part of the city plan. They are on long-term lease to management associations formed by the gardeners. Gardeners must apply through the association, but once they receive an allotment they are welcome to keep it indefinitely, as long as they pay their annual dues and plant every year. This arrangement leads to a low turnover in the allotment gardens; currently, waiting lists can be several years long.

The gardeners do not have to fight to keep their space and there is no tension over zoning or land use. This means the gardens tend not to be politicized places, which creates a very relaxing atmosphere.

One gardener likened her plot to a second living room. Permanent structures are not generally allowed, but it is not unusual to see barbeques and chairs. On any given evening, gardeners can be found relaxing in their garden. Another gardener explained that her garden was a way to “put her stress into the ground.”

The third category of UA is sack and box gardening. Started on a wide scale in 2010 by the grassroots urban vitality and environmental organization, Dodo, sack gardens create another outlet for Helsinki’s enthusiastic urban gardeners. The ease and ability to relocate a particular sack garden makes them a workable solution to plant gardens in interstitial and unexpected places. These gardens have fewer plots than the allotment gardens, the space is not generally formally leased, and there is usually a shorter waiting list. The lack of a formal lease is not a problem, because the growing space is self-contained and not dependent on the particular ground where it is placed.

Box gardens are approximately ten square feet each and serve as an example of how productive a small space can be. The box concept is similar to raised beds, but the boxes are taller so the gardener can tend the garden from a standing position. Kale and Swiss chard are some of the most popular box crops, as they are still difficult to find in supermarkets.

The most recent UA activity in Helsinki is the Kaupunkilaisten oma pelto, which translates to “city residents own field.” This is a community-supported agriculture (CSA) project started in 2011 and is referred to in English as the Herttoneimi CSA. The fields are located in the city of Vantaa, which is immediately adjacent to Helsinki. The fields are surrounded by forests and a neighborhood of single-family homes. They are also directly under one of the flight paths of nearby Helsinki International Airport. The members of the CSA rented this land and hired a farmer to produce their food.

All members of the CSA are required to perform fourteen hours of talkoot each growing season. Talkoot is a traditional concept of mutual assistance between friends and neighbors, with its origin in the countryside. Members are encouraged to perform talkoot in the way that works best for them, and talkoot activities range from fieldwork to administrative tasks. Even the youngest members are encouraged to participate as they are able, and special field days are organized for children to teach them about the origins of their food.

There are pickups on Tuesday and Wednesday in various neighborhoods of the city, which creates a space for the 200+ members to meet and visit, as well as collect their generous vegetable harvest. The food from the CSA is organic and Demeter certified (biodynamic). This is one of the few opportunities in Helsinki to purchase truly local vegetables. While these are farmers’ markets, the vendors are usually middlemen selling produce similar to what is available in the grocery stores.

From stress management, to desire for local food, to growing crops that cannot be found in the grocery store, Helsinki’s residents are enthusiastic participants in the global trend of UA. While doing fieldwork, it felt like every moment I was discovering more expressions of UA practice. Behind hedges and in boxes, Helsinki’s urban citizens are active urban growers.

I would like to thank the council of the American Geographical Society for the generous grant that supported fieldwork in the summer of 2015, and without which this research would not have been possible. I would also like to thank the urban farmers in Helsinki, who welcomed me into their fold and granted me insight into their practice. Much appreciation to my supervisors, Drs. Sarah J. Halvorson and Juha Helenius. The author took all images in this photo essay in the summer of 2015 and all persons pictured have signed appropriate releases for the use of their image. Mrs Sophia E. Hagolani-Albov is a doctoral student in agricultural sciences at the University of Helsinki, Helsinki FI-00014, Finland; [sophia.hagolani-albov@helsinki.fi].