Wildlife Conservation in Kenya and Tanzania and Effects on Maasai Communities

For many years, the Maasai communities in Kenya and Tanzania practiced nomadic pastoralism - a highly mobile cattle herding lifestyle in which the irregular wet- and dry-season climatic pulses dictated their movement in search of water and pasture. This was relatively easy as long as the management and ownership of natural resources, including water and pasture, lay in the hands of traditional communal institutions. However, the arrival of European powers changed this arrangement and imposed a system of governance based on individual land rights, wherein huge chunks of land were expropriated for the exclusive use of wildlife conservation. These changes continue to have profound social, economic, and cultural impacts to the Maasai communities, complicating conservation efforts in regions I visited in Laikipia, Kenya, conservation areas of northern Tanzania, as well as the town of Paje on the island of Unguja, part of the semiautonomous island group of Zanzibar, which is part of Tanzania.

The Ngoro Ngoro Conservation Area encompasses typical savanna grasslands, spanning both Tanzania and Kenya. This is generally a dry bioregion---rainfall of less than 100--650 mm (4--26 inches)---dominated by grass and punctuated by occasional woody plants. It serves as habitat for diverse and declining wildlife species in Africa; efforts to conserve the ecosystem and animals are still a challenge due to the evolving land-tenure system that continues to prevent nomadic migration responses to ever-changing weather patterns.

These ecosystems are also habitats to the area’s most endangered and threatened wildlife species, including big cats such as the African lions. Omnivores such as elephants, rhinos, and giraffes, as well as primates, face critical danger. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) for example, the population of African elephants dropped by 50% between 1979-2017. Several conservation models have been adopted over many decades, with varied results for both wildlife and communities. These include fortress conservation, private conservation, and community conservation.

Under early twentieth-century colonization, British governments tried to protect local wildlife through the creation of parks. Tarangire National Park---home to largest elephant population in Africa---was established in the Mara region of Tanzania under the Fauna Conservation Ordinance of 1951. While these parks continue to serve critically endangered animals, their earlier creation--- through forceful eviction of communities---created a fortress conservation model, where the longstanding dynamic of human-wildlife coexistence and sharing of resources was eliminated. Consequently, many watering points, as well as pasturelands, were completely removed from community use. This not only reduced the community’s resilience to frequent droughts in the region, but also triggered a negative perception of wildlife conservation and led to human-wildlife conflicts still witnessed today. The parks are also a continuing source of clashes between the government and communities over inequitable distribution of revenues generated from tourism.

The land-tenure system imposed by the British did not change significantly after independence in the early 1960s, as most of the land owned by Europeans was not returned to the original users. In Kenya, some of these lands were sold to private entities who later converted them to private conservancies, such as the Ol Pejeta Conservancy. This conservancy serves a critical role in the conservation of different species, including elephants and buffaloes, and is a favorite destination for tourists who want to get up close to these animals. Despite such concerted conservation efforts, the African elephant population has been drastically reduced by 30 percent between 2007-2014 due to poaching, human-wildlife conflicts, and loss of habitat.

Ol Pejeta is also a sanctuary to 115 black rhinos. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) notes that the black rhino population declined by an overwhelming 97.6 percent from 1960 to the 1990s, mainly because of poaching.

The northern white rhinos are on the verge of extinction. This picture shows one of only three remaining in the world. It is under twenty-four-hour surveillance and armed security in Ol Pejeta Conservancy.

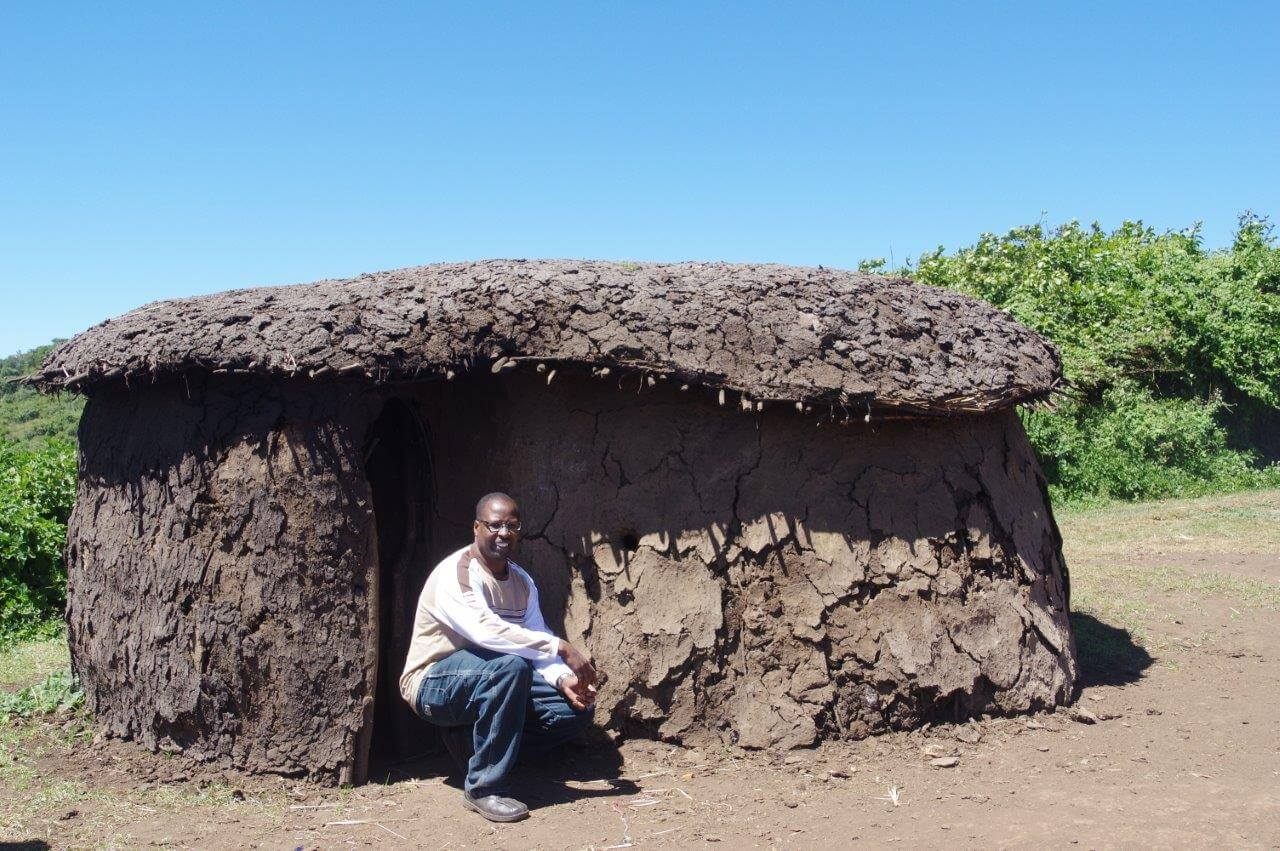

Nainokanoka manyatta (village), at the foothills of Ngoro Ngoro crater, was created to settle some of the Maasai communities evicted by the establishment of the Serengeti National Park. Such compulsory resettlement was initiated by the colonial government and reinforced by compulsory socialist ujamaa (villagization) policies of the 1970s. By the 1980s, the country had an extensive system of national parks, but wildlife populations continued to decline at an alarming rate, since the land-tenure system provided limited benefits for conservation.

A typical day in Nainokanoka village starts with young children helping to separate animals---involving the separation of lambs from sheep and kids from goats---before they are taken out to pasture. This limits trampling accidents from bigger animals, such as cows. Kids and lambs are also more vulnerable to predators.

During a community’s long-distance migration to look for pasture and water, weaker animals---including calves---are left near the village in the care of young boys. While at pasture, a bellwether animal is relied upon to alert a shepherd anytime the flock wonders from safety. A particularly greedy and adventurous goat known to keep the flock on the move is chosen and belled.

The birth of kids and lambs is carefully planned to coincide with a rainy season, which improves their survival rate because of adequate water and pasture. Mating is controlled with the aid of enjoni, a bib-like gadget made from dried animal skin and mounted around the buck’s lower body to physically prevent untimely breeding.

The creation of protected areas restricted the migratory system used by the Maasai, an adaptive mechanism that responded to the seasonal changes in weather. Thus limited, pastoralists have had to reduce their stock, thus undermining their economic wellbeing. Faced with financial hardships, young morans (Maasai warriors) have been forced to consider nontraditional ways of providing for their families, such as hawking curios and traditional jewelry on the island town of Paje in the Zanzibar archipelago, and other populous areas.

Community conservancies were introduced in the 1990s in recognition of the value of ancient community-wildlife practices that limited ill effects on both. The new conservancies also solicited community support for wildlife conservation by encouraging monetary gains through tourism and tourist-related enterprises. These pictures show giraffes at Burunge Wildlife Management Area, which is a pioneer in Tanzania’s community conservation movement. Community conservation efforts in the region have attracted these animals and generated much-needed revenue from the increase in tourism. These revenues have helped fund education, health services, and other social services in the community. Leaders from the community hosted students from University of Wisconsin-La Crosse for a question-and-answer session at one of the primary schools built and run by earnings from tourism.

Giraffe populations in Africa have declined by 40 percent in the last thirty years due to habitat loss, poaching, and civil unrest. The IUCN observed that the number of animals dropped from 163,000 in 1985 to 97,562 in 2016. Many giraffes are found outside the government national parks. Conservation by community conservancies like the Lekurruki Conservation Trust is critical.

The mutual relationship between wildlife and the nomadic lifestyle is a sustainable, ancient practice and a force behind the creation of community conservancies. Cattle are known to break up the hardpan soil in times of drought and fertilize the ground. This, in turn, allows growth of fresh grass in these areas, which then attract wildlife to the relevant conservancies, thus further boosting tourism. Such coexistence may prove to be beneficial to communities through a greater share of revenues from ecotourism.

Under community conservancies, the governments and nongovernmental organizations help communities gain access to critical water supplies. Most of the traditional watering points are within protected areas and out of bounds to communities. This picture shows pastoralists and their livestock at a watering point near the Enduiment community conservancy, west of Mt. Kilimanjaro in Tanzania.

Community conservancies encourage people to protect wildlife, as to benefit from wildlife-related enterprises supported by the visit of tourist. Here, students from the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse are shopping for artifacts at Irkeepusi cultural boma (village) in Ngoro Ngoro, Tanzania. Funds generated through such sales support the provision of social services in the communities.

Community conservancies also link culture to conservation. A tourist who travels to Nainokanoka manyatta can be entertained by the village cultural dance troupe for a small fee. Students from the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse had their share of fun while on a wildlife-conservation study tour.

Under community conservancies, government and nongovernmental organizations have helped establish livestock markets to support pastoralists. The Kimanjo market, for example, serves several community conservancies in northern Laikipia, Kenya, by facilitating an environment in which pastoralist can offer their animals---mostly sheep and goats---for sale. In this picture, pastoralists from the Naibunga Conservancy are waiting to auction off their animals to merchants from big cities.

The government also ensures that there is a ready market for livestock from the conservancies. These pictures show loaded trucks ready to ship livestock to different destinations in the country. A ready market is especially critical during drought condition, when pastoralists can lose a significant number of their animals. Similarly, the market provides a variety of agricultural food products not naturally available to pastoralists in the region

While national parks and private conservancies in Kenya and Tanzania have served to protect large numbers of threatened species, the population of these species continues to decrease precipitously. Part of the reason is the negative, indeed adversarial, impact that wildlife conservation has had on local communities. However, the creation of community conservancies has not only increased community participation in wildlife conservation, but also improved community livelihoods through such tangible benefits as monetary gains from tourism, common markets for livestock, and access to life-giving water supplies.