Postcards from Oaxaca's Past and Present *

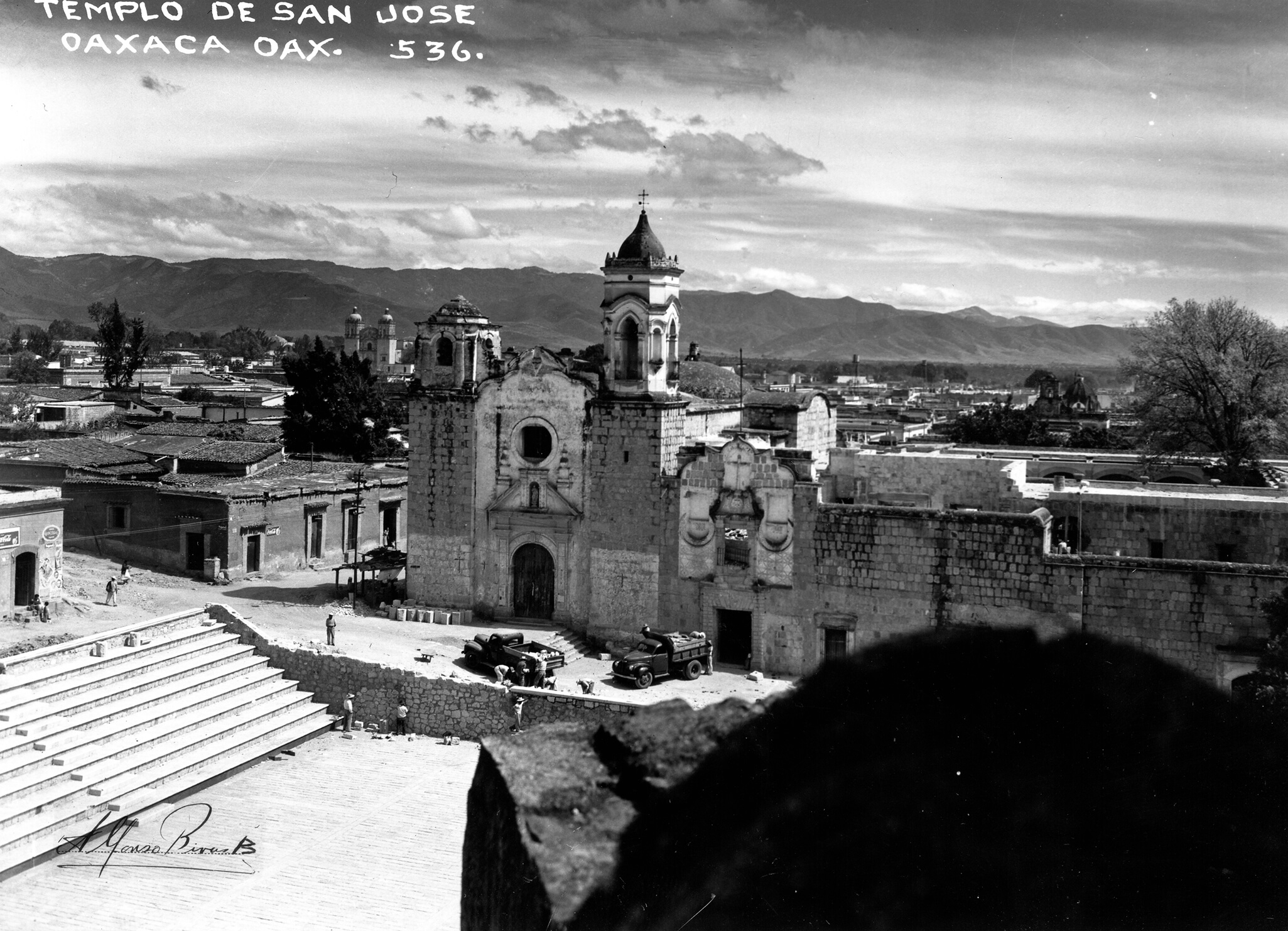

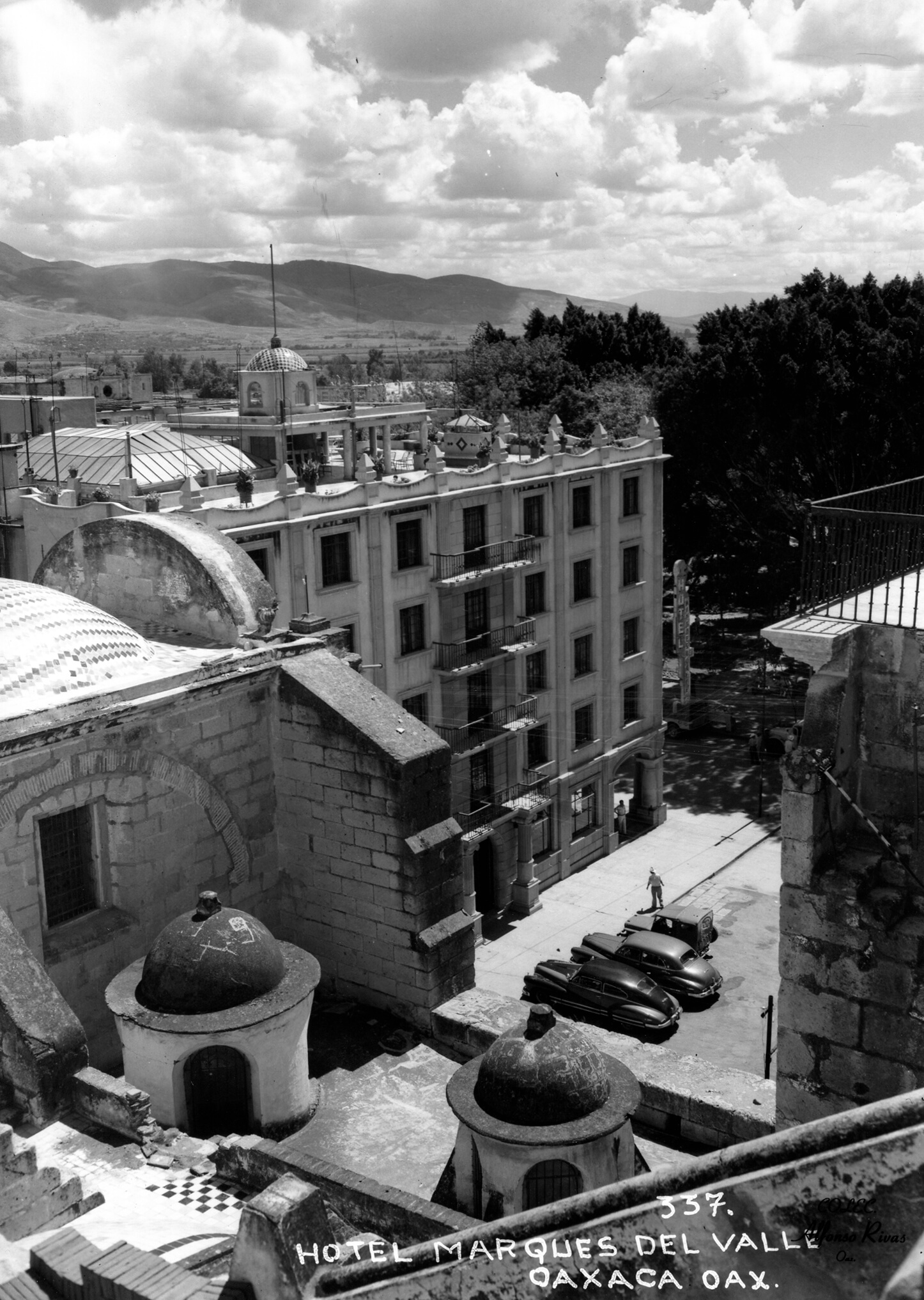

In 1942, Gustavo Bellón persuaded Mexican photographer Alfonso Rivas Bañuelos to move to Oaxaca, where Bellón sold local handicrafts and promoted tourism. He hired Rivas to take postcard photographs. Between 1942 and 1950, Rivas made over 3000 images of the city of Oaxaca. His photographs reveal what sorts of landscapes he thought would appeal to travelers and show the general outlines of the city. Rivas’ Oaxaca was a compact settlement that contained an abundance of colonial-era structures. Its borders marked a sharp transition into agricultural landscapes that filled the surrounding valley. Since Rivas took his photographs, several concomitant processes, including rapid population growth, urbanization, tourism development, modernization, and historic preservation have transformed Oaxaca. Between 2012 and 2016 I rephotographed ninety of Rivas’ images and created the following photographical pairs to show how Oaxaca’s landscapes have changed during the past seventy years.

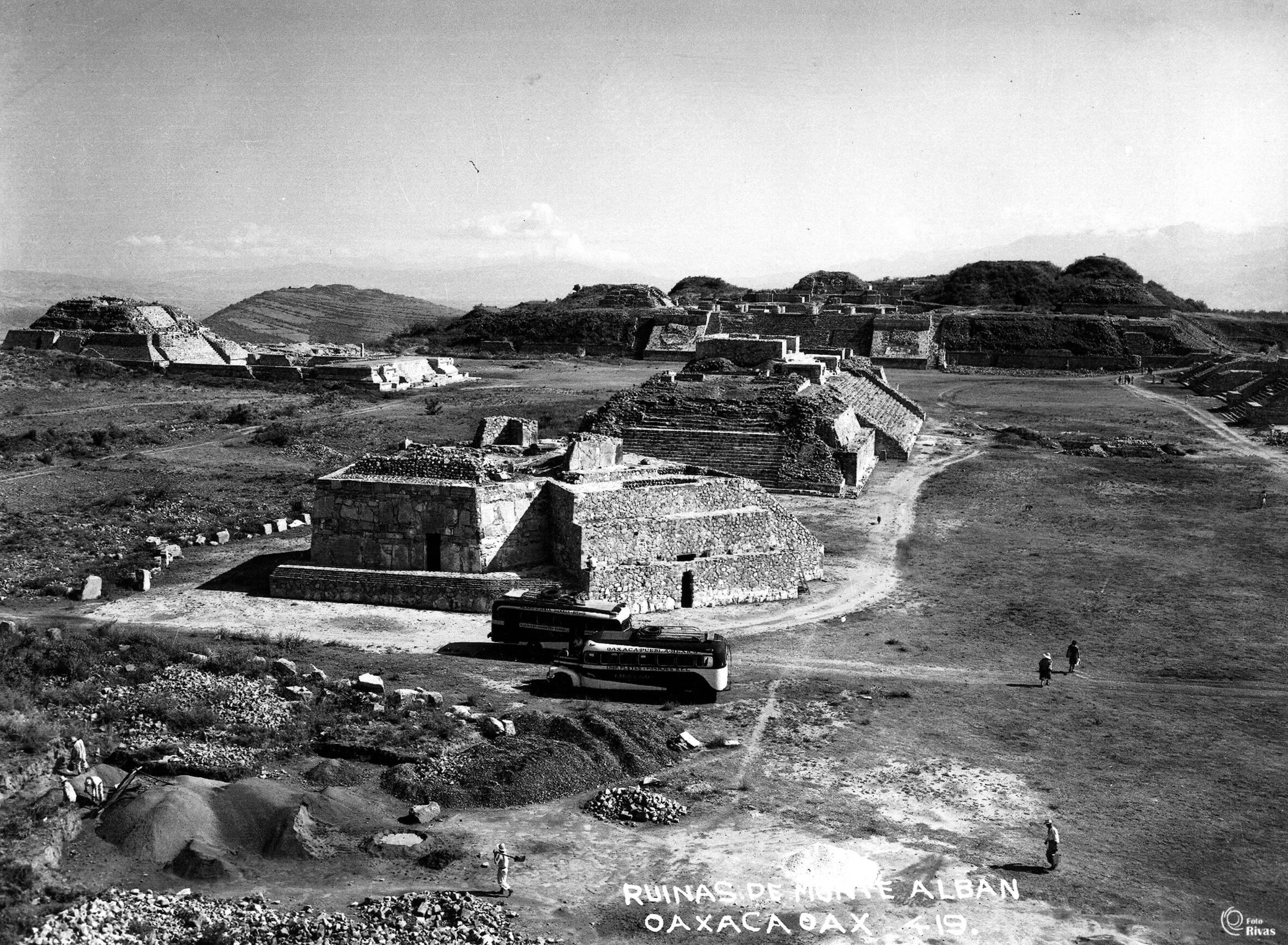

Rivas arrived in Oaxaca just ten years after Alfonso Caso began excavations at Monte Alban, the archaeological site perched 5 km west of Oaxaca’s historic core. Rivas’ photographs show ongoing reconstruction of the site. Monte Alban has since become Oaxaca’s primary tourist attraction and is protected by policies that prohibit buses from carrying visitors onto the site’s plaza.

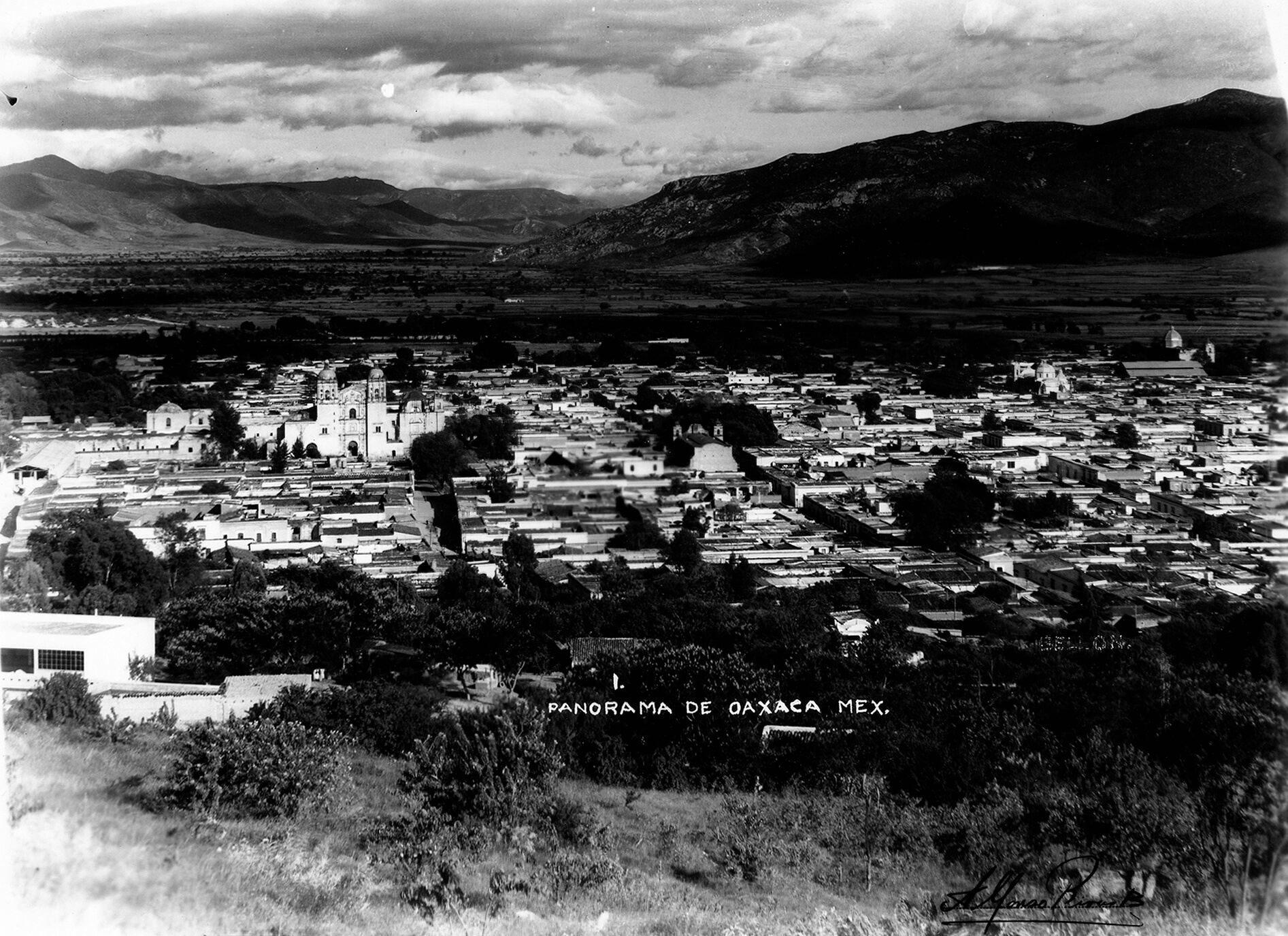

Cerro del Fortín sits 80 m above - and only 0.5 km to the northwest of - Oaxaca’s central plaza. From this point, Oaxaca’s historic core spreads out before the viewer and reveals how continuous rural to urban migration since 1945 has led to massive urban expansion, filling the valley to the east.

Northwest from Cerro del Fortín, Rivas captured a landscape dominated by the tandem curving lines of the Río Atoyac and the Pan American Highway. Channelization of the river and urban expansion into its valley hide the Atoyac. The widened highway remains, ushering automobile traffic into the city.

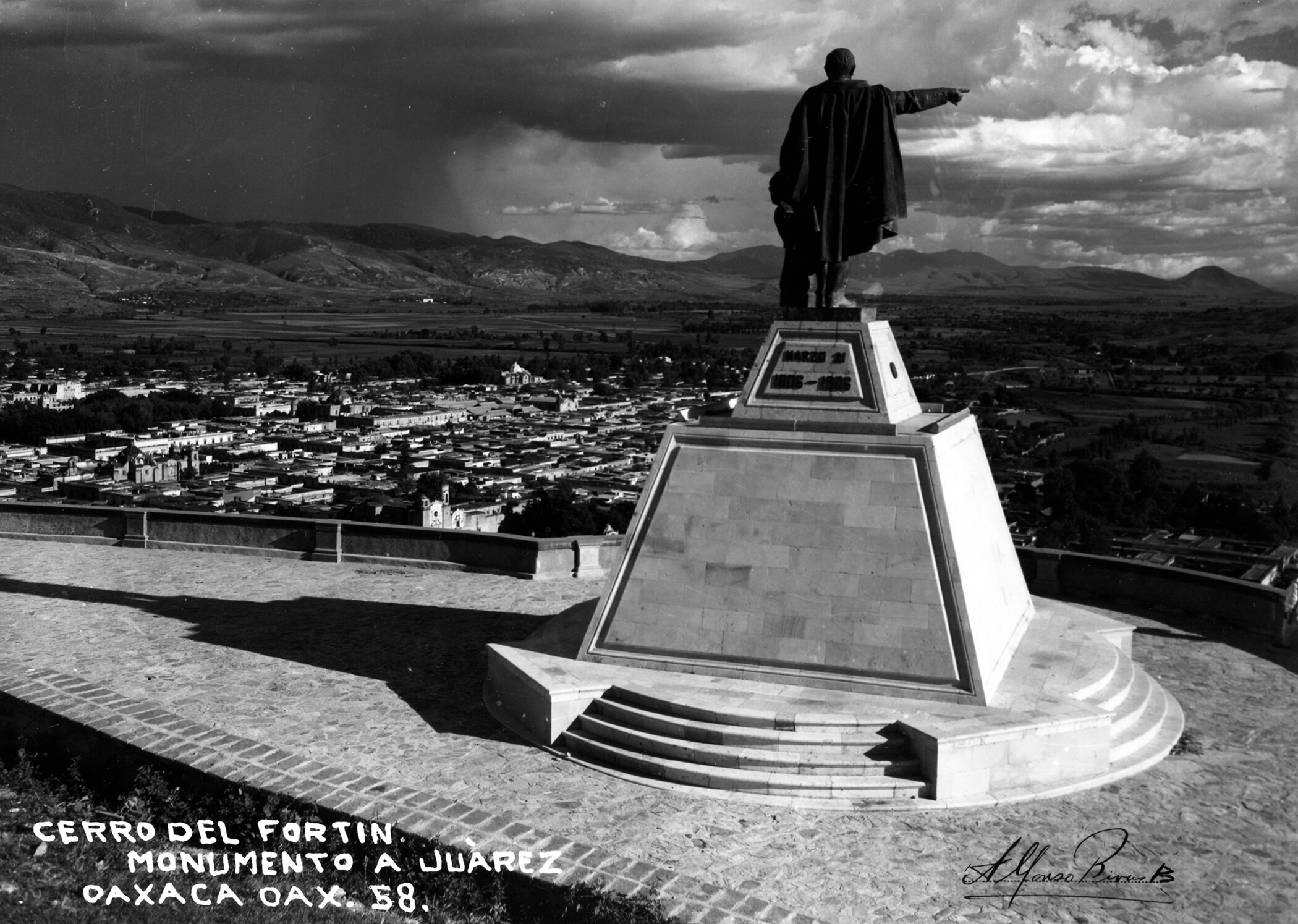

Cerro del Fortín harbors a cluster of monuments. The statue of Oaxaca’s native son, Benito Juárez, was the first. Presented to the city by the federal government in 1905 on the centennial of Juárez’s birth, the state governor placed it at Fortín to create a gateway to the city. The view highlights how urban expansion has pushed agricultural landscapes farther from the city’s historic core.

From the campanile of the Basilica de la Soledad, Oaxaca’s historic core is a choppy inland sea, punctuated by white caps comprised of the domes and steeples of colonial churches. Benito Juárez dispossessed the various Roman Catholic orders of much of their property in the 1860s. Later governments converted some of these areas into public spaces, such as Oaxaca’s Plaza de la Danza, which sits in front of the temple.

The Dominicans’ compound is Oaxaca’s grandest example of the conversion of religious property into public space and tourist attraction. The former monastery houses Oaxaca’s largest museum, the Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca. Its expansive courtyard houses Mexico’s largest ethnobotanical garden. Rather than the earlier fence, its atrium now opens onto a pedestrian street that is a popular destination for locals and visitors.

Churches, such as the Templo de San Felipe Neri, remain places of worship and, for tourists, places of interest. They also benefit from the state, federal, and city government’s commitment to historic preservation.

Completed in 1951, the Templo de los Pobres’ Rationalist design announced that Modernist ideas from Mexico City had arrived in Oaxaca City, awakening a local historic preservation movement. The city’s Colonia Reforma has since engulfed the church and made a proper repeat photograph impossible.

When it was completed in 1950, Oaxaca’s Campo Deportivo graced the northeastern edge of Oaxaca like a massive temple. Sixty-three years later, the home of Oaxaca’s professional baseball team, the Guerreros, has been swallowed by urbanization and garlanded with the bright colors of automobile traffic, McDonald’s, and graffiti courtesy of the local anarchist chapter.

The Jardín de la Bastida was difficult to shoot. The massive laurel tree is gone. The two-story facade of the university’s accounting and administration building fills in the formerly walled space. In June 2012, the canopies and umbrellas that shaded artists and itinerant vendors blocked my view. By January 2014, the city council had cleared the space and installed a bike rack to promote cycling.

Atop Oaxaca’s cathedral, Rivas photographed Oaxaca’s central plaza, the Zocalo (main square). He captured some of the space’s defining features: a restored colonial church, an arboreal oasis, and a newly constructed hotel.

The Zocalo is a center of activity for residents and visitors, its southwest corner framed by the state capitol, the Jesuits church, and the arched portales (portal, doorway). The Zocalo is a stage for restaurateurs, musicians, vendors, and visitors.

In July 2016, the Zocalo also was a stage for political protest. In this case, teachers protesting educational reform marked the second month of occupation of the Zocalo.

Rephotography guides an observer into a landscape’s past. Standing in a place with an old photograph, one looks for traces of the past and ponders how the present came to be. I walked in Alfonso Rivas Bañuelos’s footsteps looking for what he saw and chose to record, and I made my own record of Oaxaca’s landscapes. My record shows an historic core that demonstrates the complementarity of historic preservation and tourism. It also shows how that core becomes ever more distinct from the new urban landscapes that continue to spread around it. This research would not have been possible without the cooperation and aid of Doña Irma Rivas, the daughter of Alfonso Rivas Bañuelos. She provided access to the collection of her father’s photographs, taught me about his work, and gave me permission to use the photographs for my research. CSU, Chico’s College of Regional and Continuing Education, College of Behavioral and Social Sciences, and the Department of Geography and Planning provided funds that supported my fieldwork in Oaxaca. Gulliver, Eleonor, Glenn, and Annette Brady provided critical editing suggestions.